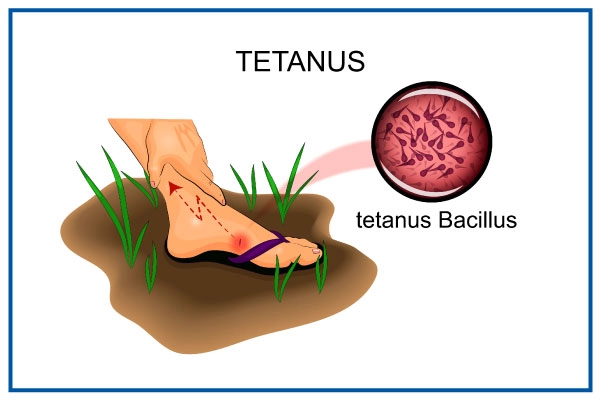

Tetanus

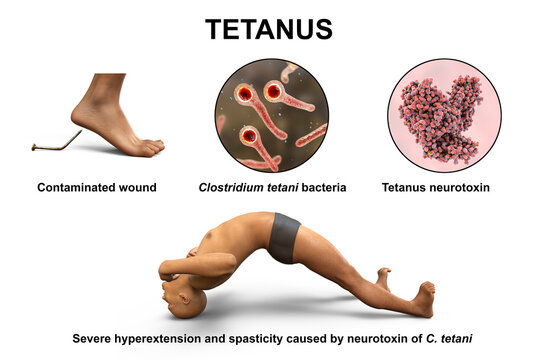

Tetanus is an acute infectious disease of the central nervous system caused by clostridium tetani and is characterized by spasms of the skeletal muscles frequently attacking the muscles of the jaw.

Tetanus is commonly known as ‘Lock-jaw.’

Cause of Tetanus

Tetanus is caused by the exotoxins of clostridium tetani.

- The organism can live for a long time in any condition, especially dirty environments. So it can be found in dust, soil, or grass.

- The clostridia can be normal organisms in the alimentary canal of animals but when passed out and gain entry to the human body, they become harmful. The organism can be found in cows, horse, sheep, or goat.

Incidence of tetanus:

- In babies born at home before arrival at the hospital.

- In homes where domestic animals are kept.

Pathophysiology of Tetanus

The pathophysiology of tetanus involves the invasion of the body by bacilli or spores, typically through deep puncture wounds or cuts. These bacilli find a suitable environment to multiply in anaerobic conditions. It is crucial to note that all unclean wounds pose a significant risk. Once the clostridium tetani organisms enter the wound, they unleash two forms of exotoxins into the surrounding tissues: tetanospasmin and tetanolysin.

Tetanospasmin, a potent toxin, plays a critical role in producing the disease’s clinical manifestations. It primarily affects the central nervous system (CNS). The toxins specifically target the motor nerve cells of the spinal cord and the brain. As a result, spasms develop in the muscles that are supplied by the corresponding nerves.

Route of entry

The route of entry for the clostridium tetani organisms includes various pathways, all of which can lead to infection and subsequent tetanus:

- Infected ulcerated wound.

- Postoperative wounds.

- Umbilical stumps (in newborns).

- Gun-shot wounds.

- Septic abortion.

- Jiggers or foreign bodies.

- Burns and scalds.

Signs and Symptoms

Tetanus manifests with a set of distinctive signs and symptoms, indicating the severity of the infection:

- Stiffness of the muscles, particularly noticeable in the jaw.

- Spasms affecting the muscles of the face, especially the cheek and jaw, leading to difficulty in opening the mouth, a condition referred to as trismus.

- The angles of the mouth are pulled outwards, causing a forced smile known as risus sardonicus or the “Devil’s grin.”

- The head is thrown back, and the back becomes arched due to the rigid muscles in the neck, a condition called opisthotonus.

- Signs of inflammation may be evident, such as swelling of the umbilical cord (if present in newborns), a wet cord, offensive smell, or pus discharge from the wound site.

- Patients may experience an elevated temperature and rapid pulse.

- Weight loss may occur due to difficulties in eating, leading to starvation.

- Spasms of the sphincters can result in retention of urine or stool, and in severe cases, sphincter rupture may occur.

- Swallowing becomes challenging as the muscles of the mouth and esophagus are affected by spasms.

- Spasms affecting the respiratory muscles may lead to prolonged periods without oxygen (anoxia), which can be life-threatening and result in death.

- Patients may have a wound or a history of a wound, which could be the point of entry for the tetanus-causing bacteria.

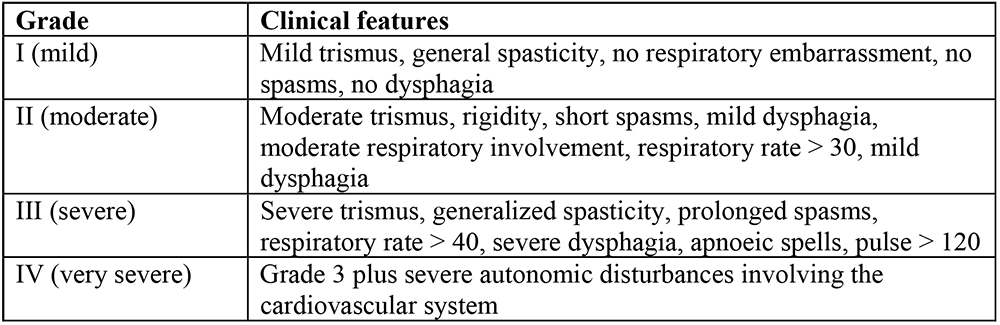

Alblett Classification of Tetanus

There are several grading systems; the scale proposed by Ablett5

is the most widely used . This categorizes patients

into four grades depending upon the intensity of spasms, and

respiratory and autonomic involvement.

Management of Tetanus

There’s no cure for tetanus. A tetanus infection requires emergency and long-term supportive care while the disease runs its course.

Aims of Management

- To control spasms.

- To eliminate the causative organism and its toxins.

- To prevent complications, and ensure adequate nutrition for the patient.

Specific treatment measures include:

Penicillin: Administering penicillin is a crucial step in destroying the tetanus-causing organism.

Anti-tetanus serum: The administration of anti-tetanus serum helps neutralize the spreading toxins and halt their further detrimental effects.

Sedation and muscle relaxants: Medications like diazepam and chlorpromazine are given to provide sedation and muscle relaxation, effectively alleviating spasms and minimizing discomfort.

Wound management: If there is a wound or focus of infection where the tetanus bacteria may have entered, the dead tissue is excised, and the area is irrigated with hydrogen peroxide. Leaving the wound open without suturing promotes oxygen exposure, hindering the growth of tetanus bacilli, which thrive in anaerobic conditions.

Control of spasms involves the following measures:

- Absolute rest and isolation: The patient should be kept in a quiet room with dim lighting to minimize triggers for spasms.

- Prevention of external stimuli: Measures such as fitting the door with suitable closing materials or springs prevent slamming noises that could stimulate the patient.

- Warming hands before touching: Nurses should warm their hands before touching the patient to avoid any stimulation that might trigger spasms.

- Medication administration: Sedatives and muscle relaxants, such as chlorpromazine (Largactil), and Diazepam, are given regularly through a nasogastric tube to maintain a controlled state and alleviate spasms.

o Example of 6 hourly regimen

Drug

6-9

am

9-12

pm

12-3

pm

3-6

pm

6-9

pm

9-12

am

12-3

am

3-6

am

6-9

am

Largactil

✔

⫼⫼⫼⫼

✔

⫼⫼⫼⫼

✔

⫼⫼⫼⫼

✔

⫼⫼⫼⫼

✔

Diazepam

⫼⫼⫼⫼

✔

⫼⫼⫼⫼

✔

⫼⫼⫼⫼

✔

⫼⫼⫼⫼

✔

⫼⫼⫼⫼

General Management:

Close observation and airway management: Monitor the patient closely, ensuring a clear airway and using a mucous extractor if necessary.

Vital signs monitoring: Regularly check temperature, pulse, and respirations, noting the severity of the condition. Record the strength, frequency, duration, and body part involved in spasms using a spasm chart.

Nutrition: Maintain adequate nutrition through nasogastric tube feeding to avoid stimulating spasms with injections. Prevent aspiration of fluids into the airway.

Catheterization: Catheterize the patient to maintain proper bladder function.

Fluid balance chart: Monitor and maintain fluid balance, initially using intravenous fluids if necessary and later transitioning to nasogastric tube feeding.

Hygiene: Ensure daily cleaning of the cord with normal saline and perform oral care carefully. Turn the patient every two hours to prevent pressure sores.

Vaccination: Prevent future tetanus cases by ensuring all individuals receive a full course of DPT (diphtheria, pertussis, and tetanus) vaccination.

Use sterile equipment: Prevent cross-infection by using sterile equipment during medical procedures.

Bowel and bladder care: Monitor and assist the patient in passing stool and urine.

Medication: Administer prescribed drugs as instructed.

Physiotherapy: Implement physiotherapy sessions for deep breathing exercises and active limb movements.

Prevention:

Public health education: Raise awareness about the dangers of using unsterilized equipment during childbirth and applying native medicine or other substances to the umbilical cord.

Immunization: Ensure that all women of childbearing age are vaccinated against tetanus.

Safe childbirth practices: Promote safe and clean practices during childbirth to prevent infections.

Discourage harmful practices: Discourage practices like applying cow dung to a child’s umbilical cord.

Wound care education: Educate people on cleaning wounds thoroughly with water and soap to prevent infections. Encourage covering wounds with sterile dressings and seeking early medical attention for cut wounds.

Protective gear: Encourage the use of gum boots when digging to prevent soil-related infections.

Complications of Tetanus

Fracture of bones or the spine: The intense and frequent muscle spasms can cause fractures in bones or the spine, especially if the spasms are severe and uncontrolled.

Pneumonia: Heavy sedation, a common treatment for managing tetanus spasms, may lead to shallow breathing or difficulty in clearing the airway, increasing the risk of pneumonia, a potentially severe respiratory infection.

Brain damage: The potent toxins produced by the tetanus-causing bacteria can affect the central nervous system, leading to brain damage in severe cases.

Growth retardation: In children affected by tetanus, the disease can interfere with proper nutrition and growth, potentially causing growth retardation.

Exhaustion: The continuous and strenuous muscle spasms can lead to extreme exhaustion, further weakening the patient’s overall condition.

Respiratory failure: In severe cases, the spasms can affect the respiratory muscles, resulting in respiratory failure, where the patient is unable to breathe adequately on their own.

Retention of urine: Spasms in the pelvic region can cause the sphincters to contract, leading to difficulty in passing urine and possible urine retention.

Death due to airway obstruction: In the most severe cases, the intense spasms, particularly those affecting the muscles of the jaw and neck, can obstruct the airway, leading to suffocation and potential death.

Test Questions

Which bacterium causes tetanus?

a) Streptococcus pyogenes

b) Staphylococcus aureus

c) Clostridium tetani

d) Escherichia coli

Answer: c) Clostridium tetani

Explanation: Clostridium tetani is the bacterium responsible for causing tetanus.

What is the common term used to describe tetanus due to spasms in the jaw muscles?

a) Trismus

b) Opisthotonus

c) Risus sardonicus

d) Tetanospasmin

Answer: a) Trismus

Explanation: Trismus is the medical term for difficulty in opening the mouth due to jaw muscle spasms, which is commonly known as “Lock-jaw.”

What is the primary goal of managing tetanus?

a) Preventing complications

b) Destroying the toxin

c) Controlling fever

d) Alleviating pain

Answer: a) Preventing complications

Explanation: The main aim of managing tetanus is to prevent complications associated with the disease and ensure the best possible outcome for the patient.

What is the specific treatment given to destroy the tetanus-causing organism?

a) Penicillin

b) Paracetamol

c) Aspirin

d) Ibuprofen

Answer: a) Penicillin

Explanation: Penicillin is administered to destroy the Clostridium tetani bacterium responsible for causing tetanus.

Which complication of tetanus can lead to respiratory failure?

a) Pneumonia

b) Fracture of bones

c) Brain damage

d) Respiratory muscle spasms

Answer: d) Respiratory muscle spasms

Explanation: Tetanus-induced spasms affecting the respiratory muscles can lead to respiratory failure, where the patient is unable to breathe adequately on their own.

Why is the use of a mucous extractor important in tetanus management?

a) To prevent dehydration

b) To clear the airway

c) To alleviate muscle spasms

d) To prevent fever

Answer: b) To clear the airway

Explanation: A mucous extractor is used to clear the airway and prevent obstruction caused by excessive secretions, which is crucial in tetanus management.

What is the recommended method for feeding tetanus patients to avoid spasms triggered by injections?

a) Intravenous feeding

b) Nasogastric tube feeding

c) Oral feeding

d) Intramuscular injections

Answer: b) Nasogastric tube feeding

Explanation: Nasogastric tube feeding is used to provide nutrition and administer drugs to tetanus patients while avoiding the stimulation of spasms caused by intramuscular injections.

Which immunization should be given to prevent future tetanus cases?

a) Hepatitis B

b) Measles, Mumps, and Rubella (MMR)

c) Diphtheria, Pertussis, and Tetanus (DPT)

d) Polio

Answer: c) Diphtheria, Pertussis, and Tetanus (DPT)

Explanation: The DPT vaccine provides immunity against diphtheria, pertussis (whooping cough), and tetanus, preventing future tetanus cases.

What measure can be taken to prevent tetanus in newborns with umbilical stumps?

a) Cleaning the stump with cow dung

b) Applying native medicine on the stump

c) Keeping the stump dry and clean

d) Ignoring the stump until it falls off naturally

Answer: c) Keeping the stump dry and clean

Explanation: Maintaining cleanliness and dryness of the umbilical stump can prevent infection and the risk of tetanus in newborns.

What is the purpose of physiotherapy in tetanus management?

a) To provide pain relief

b) To promote muscle strength

c) To control spasms

d) To increase body temperature

Answer: b) To promote muscle strength

Explanation: Physiotherapy aims to promote muscle strength and mobility, which can be helpful in the recovery process of tetanus patients.