Table of Contents

ToggleCholera

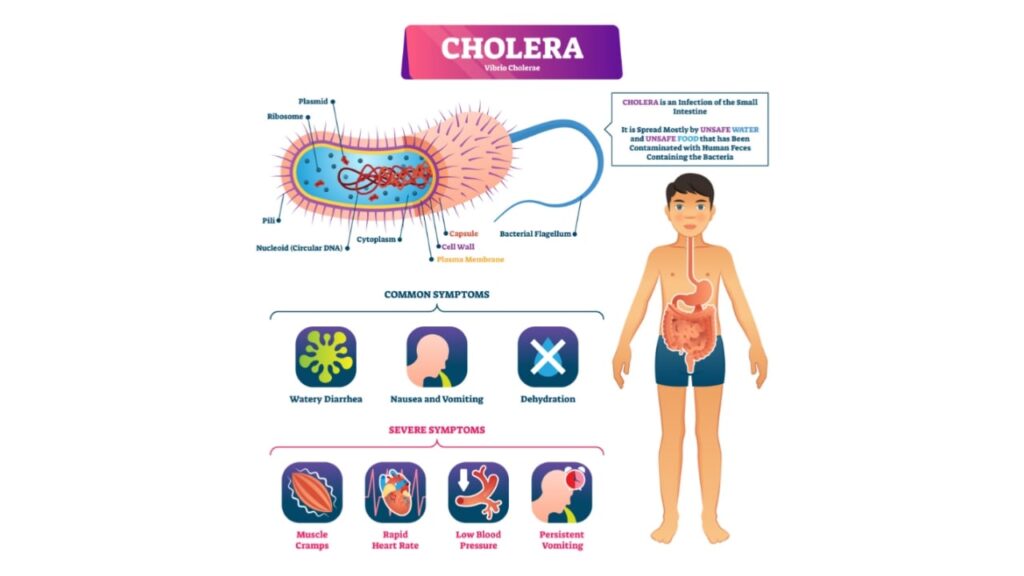

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine caused by the bacterium Vibrio cholerae.

Cholera is a serious, acute intestinal diarrheal disease characterized by a sudden onset of profuse watery stools, severe vomiting, rapid dehydration, acidosis, and circulatory collapse.

If left untreated, death can occur within a few hours after the onset of symptoms. Cholera is an internationally notifiable disease, meaning it must be reported to authorities, and it can spread to any part of the world.

The infection is characterized by profuse watery stools, vomiting, dehydration, and collapse.

Cause

- Vibrio cholerae: This comma-shaped, gram-negative bacterium is responsible for cholera. It is aerobic or facultatively anaerobic, motile (using flagella), and thrives in alkaline environments (pH 8.0). It grows best at 30-40°C, but dies in acidic media or at temperatures below or above this range.

- This bacterium is Gram stain negative and possesses a flagellum, a long projecting part that enables it to move, and pili, hair-like structures that it uses to attach to the intestinal tissue.

Mode of Spread

- Fecal-Oral Route: The most common route of transmission is through contaminated water and food, which occurs when feces from an infected person contaminate water sources or food.

- Ingestion of Contaminated Food: Ingesting food contaminated with infected water can lead to infection.

- Direct Contact: Direct contact with an infected person, particularly without proper hygiene, can transmit the disease.

Carriers: Carriers of the bacteria, even if they are asymptomatic, can spread the disease to others.

Susceptibility: Several factors influence the susceptibility to cholera:

Ingestion of bacteria: In a normal, healthy adult, approximately 100 million bacteria must typically be ingested to cause cholera. This highlights the importance of a significant bacterial load for infection to occur.

Age: Children, particularly those between the ages of two and four, are more susceptible to cholera infection. This could be attributed to their underdeveloped immune systems and increased likelihood of exposure due to their behavior and hygiene practices.

Lowered immunity: Individuals with weakened immune systems, such as those with AIDS or malnourished children, are at higher risk of experiencing severe cases if they become infected with cholera. Their compromised immune function makes it more difficult for their bodies to fight off the infection effectively.

Pathology

- Intestinal Colonization: Vibrio cholerae colonizes the small intestine and multiplies rapidly.

- Enterotoxin Production: Vibrio cholerae produces cholera toxin, which doesn’t invade the intestinal mucosa or enter the bloodstream.

- Fluid Secretion: The toxin disrupts the normal function of intestinal epithelial cells, causing them to secrete large amounts of fluids and electrolytes into the intestinal lumen. This results in profuse watery diarrhea.

- Dehydration: The loss of fluids and electrolytes leads to severe dehydration. The body tries to compensate by drawing fluids from other areas, leading to:

- Dry Skin and Mucous Membranes: The skin becomes dry, and the mucous membranes (including the eyes, mouth, and tongue) become dry.

- Thickening of Blood: Blood becomes more viscous due to fluid loss.

- Collapsed Vessels: Blood vessels collapse due to low blood volume.

- Muscle Cramps: Severe muscle cramps result from electrolyte loss.

- Lung Failure: The lungs become dry and may fail due to dehydration.

- Organ Failure: Other organs can fail as a result of severe dehydration and electrolyte imbalance.

Pathophysiology of Cholera

Cholera is a gastrointestinal illness caused by the bacterium Vibrio cholerae. The bacteria produce a toxin that causes the body to lose water and electrolytes, leading to severe diarrhea.

How the Bacteria Enter the Body

Most Vibrio cholerae bacteria are killed by the acidic environment of the stomach. However, a small number of bacteria can survive and travel to the small intestine. The bacteria attach to the intestinal wall and produce a toxin that causes the body to lose water and electrolytes.

The Toxin

The toxin produced by Vibrio cholerae is called cholera enterotoxin. The toxin binds to cells in the small intestine and activates an enzyme that causes the cells to pump water and electrolytes into the intestine. This results in the production of large amounts of watery diarrhea.

More Detailed Pathophysiology:

Upon consumption, most Vibrio cholerae bacteria do not survive the acidic conditions of the human stomach. However, a small number of bacteria manage to survive. As they exit the stomach and reach the small intestine, they need to navigate through the thick mucus lining in order to reach the intestinal walls, where they can establish themselves and multiply. Vibrio cholerae bacteria possess flagella for mobility and pili to attach to the intestinal tissue.

Vibrio cholerae bacteria produce a toxin that is responsible for causing the most severe symptoms of cholera. This toxin, known as an enterotoxin, acts on human cells, prompting them to extract water and electrolytes from the body, primarily from the upper gastrointestinal tract. The extracted fluid and electrolytes are then pumped into the intestinal lumen, resulting in the excretion of diarrheal fluid.

Clinical Picture/Signs and Symptoms

The incubation period for cholera is usually 2-3 days. The first signs and symptoms of cholera are watery diarrhea and vomiting. The diarrhea can be so profuse that it can lead to dehydration and shock.

In a typical case of severe cholera, the disease progresses through three stages:

First Stage (Diarrheal Stage)

- Onset: This stage lasts for 3 to 12 hours.

- Profuse, Watery Diarrhea: The hallmark of cholera is the sudden onset of watery diarrhea, which can be profuse, ranging from several liters to 10 liters per day. The stool resembles rice water, a thin, milky white fluid that may contain flecks of mucus.

- Vomiting: Vomiting may be frequent and can be severe, further contributing to dehydration.

- Muscle Cramps: Muscle cramps, particularly in the legs and abdomen, are common due to electrolyte loss.

- Mild Dehydration: Initially, dehydration is mild, but it can progress rapidly if not addressed promptly.

Second Stage (Collapse Stage)

- Rapid Dehydration: This stage develops within 6 to 12 hours.

- Increased Fluid Loss: Diarrhea and vomiting worsen, leading to rapid fluid loss and severe dehydration.

- Thirst and Weakness: Intense thirst and general weakness become prominent.

- Sunken Eyes and Dry Mucous Membranes: As dehydration progresses, sunken eyes and dry mucous membranes (mouth, tongue, eyes) are evident.

- Skin Turgor and Skin Elasticity: Skin becomes dry and wrinkled, and skin turgor (the ability of the skin to return to its original shape after being pinched) is decreased.

- Hypovolemia (Low Blood Volume): The decrease in blood volume leads to a rapid heartbeat, low blood pressure, and a weak pulse.

- Hypotension (Low Blood Pressure): Hypotension can be profound, and blood pressure becomes difficult to measure.

- Rapid Breathing: The body compensates for fluid loss by increasing the respiratory rate.

- Electrolyte Imbalance: Loss of electrolytes (sodium, potassium, chloride, bicarbonate) can cause muscle cramps, fatigue, and confusion.

- Acidosis (Increased Acid in Blood): Dehydration can lead to metabolic acidosis, which can cause rapid breathing, confusion, and lethargy.

- Hypoxia: Lack of oxygen to the brain due to reduced blood flow can cause lethargy, confusion, and coma.

Third Stage (Shock Stage)

- Life-Threatening: This stage is life-threatening, and immediate medical intervention is essential.

- Circulatory Collapse: Severe dehydration leads to a collapse of the circulatory system, resulting in shock.

- Rapid Heartbeat: The heart races in an attempt to maintain blood pressure.

- Weak Pulse: The pulse becomes weak and rapid.

- Low Blood Pressure: Blood pressure drops significantly.

- Altered Mental Status: Confusion, lethargy, and coma are common.

- Kidney Failure: Dehydration can lead to kidney failure.

- Respiratory Failure: Severe dehydration can cause respiratory failure.

Diagnosis of Cholera

The diagnosis of cholera is based on the following:

- History: The patient may have a history of travel to an area where cholera is common, or they may have been in contact with someone who has cholera.

- Symptoms: The patient will typically have watery diarrhea and vomiting. The diarrhea may be so profuse that it can lead to dehydration and shock.

- Physical examination: The doctor will examine the patient for signs of dehydration, such as dry skin, sunken eyes, and decreased urination.

- Laboratory tests: The following laboratory tests may be performed to diagnose cholera:

- Stool culture: This test is used to grow the bacteria in the laboratory.

- Polymerase chain reaction (PCR): This test is used to detect the genetic material of the bacteria.

- Rapid diagnostic test (RDT): This test is a rapid way to detect the bacteria.

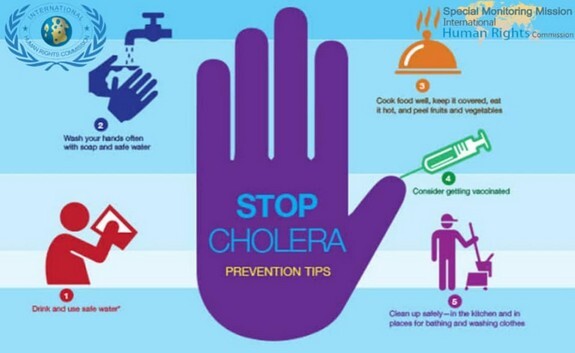

Prevention of Cholera

Cholera is a serious disease that can be fatal, but it is preventable. The best way to prevent cholera is to follow proper sanitation practices.

Here are some specific steps you can take to prevent cholera:

Hand hygiene: Always wash hands with water and soap before preparing, serving, or consuming food. Additionally, it is important to wash hands with soap and water after using a latrine.

Safe drinking water: Boil all drinking water or treat it with chlorine. Store the treated water in a clean container to prevent recontamination.

Food safety: Consume food when it is still hot. If consuming raw foods such as fruits and vegetables, ensure they are properly washed, and when possible, peeled before eating.

Food storage: Cover all foods to prevent contamination by dust, house flies, and cockroaches.

Reporting and burial practices: In the unfortunate event of a cholera-related death, report it immediately to health authorities. Burial should take place promptly, and it is crucial to avoid serving food during this time.

Surveillance and reporting: Active surveillance and prompt reporting of suspected cases allow for the rapid containment of cholera epidemics.

Disinfection: Kill the germs by sprinkling germ-killing solutions, such as JIK, on stool or vomitus, as well as on any other materials used by the person suffering from cholera.

Water and sanitation improvement: Enhance water and sanitation infrastructure to reduce the transmission of infection, such as by improving access to clean water sources and implementing proper waste management systems.

Outbreak investigations: Conduct thorough investigations of diarrheal outbreaks to identify the source of contamination and implement appropriate control measures.

Cholera vaccination: Consider immunization with cholera vaccines in areas prone to outbreaks or for individuals at high risk of exposure.

Treatment of malnutrition: Address malnutrition, as individuals with weakened immune systems are more susceptible to severe cholera. Providing adequate nutrition can help improve their overall resilience.

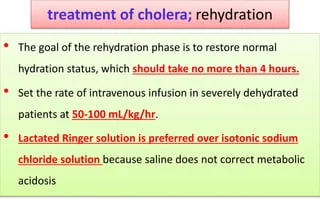

Management and Treatment

- Patient admission: The patient can be admitted to temporary hospitals, schools, or churches. Cholera beds with a central hole are used, allowing continuous stools to pass into a calibrated bucket containing a disinfectant.

- Oral Rehydration Solution (ORS): ORS is the primary treatment for cholera. It is recommended for rehydrating patients and replenishing electrolytes lost through diarrhea. In cases of severe dehydration, intravenous Ringer’s lactate or normal saline, along with ORS, may be administered. The patient should be reassessed every one to two hours, and hydration should be continued. If there is no improvement in hydration, the intravenous drip rate may be increased. During the first 24 hours of treatment, the patient may require 200ml/kg or more of fluid. If hydration improves and the patient is able to drink, switching to ORS solution is recommended.

- Nasogastric tube: In young children, a nasogastric tube can be used to administer fluids if necessary, ensuring adequate hydration.

- Antibiotics: In certain cases, antibiotics may be prescribed. Doxycycline 300mg or ciprofloxacin as a single dose can be given, but they are contraindicated in pregnancy. For pregnant women, septrin can be used. In children, cotrimoxazole, doxycycline, ciprofloxacin, or erythromycin may be considered based on the specific circumstances.

- Hypoglycemia management: If hypoglycemia is present, intravenous dextrose should be administered to correct low blood sugar levels.

- Zinc supplementation: Zinc supplementation is effective in treating and preventing diarrhea, especially among children. It can be provided to aid in recovery.

- Isolation and infection control: Patients should be isolated to prevent the spread of infection, as stools and vomit are highly infectious. Proper disposal of stools and vomit should be carried out, preferably into a pit latrine.

- Equipment and instrument disinfection: Hospital equipment should be cleaned with a disinfectant such as JIK. Instruments can be cleaned with JIK or sterilized to prevent the transmission of the infection.

- Fluid balance chart: A fluid balance chart should be instituted to monitor the patient’s hydration status closely.

Cholera Management:

Cholera is a medical emergency so prompt response should be initiated.

AIMS:

- Immediate Reduction of Electrolyte and Fluid Loss: This is the primary goal, ensuring the patient’s survival.

- Prevention of Infection Spread: Strict isolation measures are essential to prevent the spread of cholera within the healthcare setting and community.

- Notification of Authorities: Promptly informing authorities about the outbreak is crucial for public health measures.

- Elimination of Bacteria: Antibiotics are used to reduce the bacterial load and shorten the duration of illness.

- Patient and Public Education: Raising awareness about cholera, its transmission, prevention, and proper management is essential for the community.

ACTIONS:

FIRST AID:

- Reception: Properly protected healthcare personnel assess the patient’s airway, breathing, circulation (ABCs), signs and symptoms of dehydration (sunken eyes, dry mucous membranes, skin turgor), level of consciousness, and vital signs.

- Immediate IV Line: Establish an intravenous line and begin fluid replacement with Ringers Lactate (R/L), Dextrose 5%, or Normal Saline, adjusting the rate according to the severity of dehydration.

- Positioning and Oxygen: Place the patient in a comfortable position and provide oxygen therapy if necessary.

- Hygiene: Ensure proper hygiene for the patient, including clean clothes, skin, and perineum.

- History Taking: Gather detailed history, including the duration and severity of diarrhea and vomiting, level of consciousness, vital signs, and any relevant medical information.

- Doctor’s Orders: Follow the doctor’s orders meticulously.

- Treatment of Shock: Administer intravenous fluids as prescribed, usually starting with a rapid bolus of 100ml/kg over 30 minutes, followed by 70ml/kg over 2.5 hours. Reassess the patient’s response within 30 minutes to 1 hour. If there is no improvement, increase the rate of fluid administration.

- Oxygen Therapy: Provide oxygen therapy as needed.

ADMISSION:

- Isolation: Isolate the patient in a designated cholera bed with a central hole and bucket placed underneath for proper waste disposal.

- Personal Protective Equipment: Healthcare personnel must wear appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) when caring for the patient, including aprons, masks, isolation gowns, caps, gumboots, and disposable gloves. Explain the rationale for these measures to the patient.

- District Health Authority: Inform the district health authority about the case for prompt public health action.

DRUGS:

Antibiotics:

- Doxycycline: 300mg single dose OR

- Ciprofloxacin: 1gm stat OR

- Erythromycin: 62.5 to 250mg every 6 hours for 5 days OR

- Ciprofloxacin: 20mg/kg single dose for children.

FREQUENT ASSESSMENT:

- Vital Signs: Monitor vital signs every 15 minutes initially, then every 30 minutes, 1 hour, and 4 hours until discharge.

- Dehydration Signs: Assess signs and symptoms of dehydration every 30 minutes, reclassify the severity, and adjust treatment accordingly.

- Level of Consciousness: Observe the patient’s level of consciousness for signs of drowsiness, weakness, or confusion.

- Fluid Output: Measure and record the volume, frequency, consistency, and characteristics of diarrhea and vomiting.

OTHER IMMEDIATE CARE:

Infection Control:

- Disinfection: Disinfect all stool and vomitus with 1% sodium hypochlorite (JIK) before discarding.

- Hygiene: Thoroughly clean and disinfect bedpans, buckets, urinals, and other contaminated items.

- Patient Hygiene: Maintain patient hygiene by cleaning the skin, mouth, perineum, and providing padding as needed.

- Linen Care: Soak contaminated linen in JIK for 2 to 6 hours, scrub thoroughly, place in labeled linen bags, and transport to the laundry for further disinfection.

- Waste Disposal: Dispose of excreta and food remains after measurement and recordkeeping.

- Utensil Care: Ensure the proper cleaning and disinfection of utensils.

- Safe Water: Provide safe, boiled, and treated water for drinking and cooking.

- Food Preparation: Ensure proper cooking of food and water treatment before consumption.

- Environmental Hygiene: Thoroughly scrub sinks, equipment, and the patient’s room, labeling the room “Infectious, No Entry”.

- Avoid Direct Contact: Minimize direct contact with patient’s waste.

DIET:

- Parenteral Nutrition: Provide parenteral nutrition (IV or NG tube) in severe cases.

- Fluid Diet: Start with a fluid diet (plenty of fluids) to rehydrate.

- Light Diet: Gradually transition to a light, nourishing, well-balanced, non-irritating diet, considering the patient’s preferences and financial situation.

- Normal Diet: Once the patient is stable, progress to a normal diet.

REHABILITATION/PHYSIOTHERAPY:

- Passive ROM: Initiate passive range of motion exercises (ROM) while the patient is still in bed.

- Active ROM: Encourage active sitting up in bed, moving to a chair, and walking around the room and outside for fresh air.

- Reassurance: Continuously reassure the patient about their condition and their role in their recovery.

- Health Teaching: Educate the patient about cholera:

- Definition, causes, and mode of transmission

- Importance of handwashing in infection control

- Personal, community, and environmental sanitation or hygiene

- Food and water hygiene and protection of water sources

- Vector control using insecticide sprays

- Reporting of new cases immediately

- Mass screening, isolation, and treatment of suspected cases.

- Limiting the use of equipment shared by infected individuals (showers, toilets, basins).

DISCHARGE:

- Full Information: Discharge the patient with comprehensive information and follow-up dates.

- Advice: Advise the patient on:

- Adequate fluid intake

- Good nutrition

- Consumption of only safe food and water

Complications

- Severe Dehydration and Vascular Collapse: This is the most serious complication of cholera, leading to circulatory shock and potentially death.

- Electrolyte Imbalance and Acidosis: Severe fluid loss can disrupt electrolyte balance, leading to acidosis and potentially organ damage.

- Shock: Dehydration can cause circulatory shock, a life-threatening condition.

- Organ Failure: Dehydration and electrolyte imbalances can lead to heart, kidney, liver, and lung failure.

- Hypoxia and Brain Malnutrition: Dehydration can cause hypoxia (lack of oxygen to the brain), leading to seizures, coma, and death.

- Gangrene: Extreme fluid loss can lead to gangrene in the extremities due to reduced blood flow.

- Hypostatic Pneumonia: Bedridden patients are at risk for hypostatic pneumonia due to reduced lung capacity.

- Tetany: Electrolyte imbalances can lead to tetany, characterized by muscle spasms and seizures.

- Acidosis: Dehydration and electrolyte imbalance can cause acidosis, a dangerous condition.

- Abortion and Intrauterine Fetal Death: Severe diarrhea in pregnant women can increase intra-abdominal pressure, potentially leading to miscarriage or fetal death.

Prevention

- Safe Water: Access to safe drinking water is crucial. Boiling water for 1 minute can kill Vibrio cholerae.

- Handwashing: Frequent handwashing with soap and water, especially after using the toilet and before handling food, is essential.

- Safe Food Handling: Proper food handling practices, such as cooking food thoroughly and storing it properly, can help prevent cholera.

- Sanitation: Adequate sanitation facilities, such as latrines and sewage systems, are crucial for preventing the spread of cholera.

- Vaccination: Oral cholera vaccines are available and provide partial protection against cholera infection. However, they are not always effective and require boosters for long-term protection.

Related Question

- a) List 5 cardinal signs and symptoms of cholera.

- b) Outline 10 specific nursing care in an outbreak of cholera.

Solutions

a) Five cardinal signs and symptoms of cholera include:

- Watery diarrhea, sometimes in large volumes.

- Nausea and vomiting.

- Dehydration.

- Rice-water stools.

- Loss of skin elasticity.

b) Ten specific nursing care measures in an outbreak of cholera:

- Wash hands with soap and running water frequently, especially after using the toilet and before handling food.

- Advise people to drink only safe water, such as bottled water or water that has been boiled.

- Encourage individuals to consume food that is fully cooked and hot, and to avoid street vendor food whenever possible.

- Discourage the consumption of sushi, as well as raw or improperly cooked fish and seafood.

- Monitor intake and output, taking note of the number, character, and amount of stools.

- Promote the use of latrines or proper disposal of feces, emphasizing not to defecate in any body of water.

- Ensure that any articles used are properly disinfected or sterilized before use.

- Maintain strict asepsis during dressing changes, wound care, intravenous therapy, and catheter handling.

- Practice hand hygiene by washing hands or using hand sanitizer before and after having contact with the patient.

- Implement proper waste management procedures, particularly for human excreta.

Thanks for this notes

its really extensive thanks