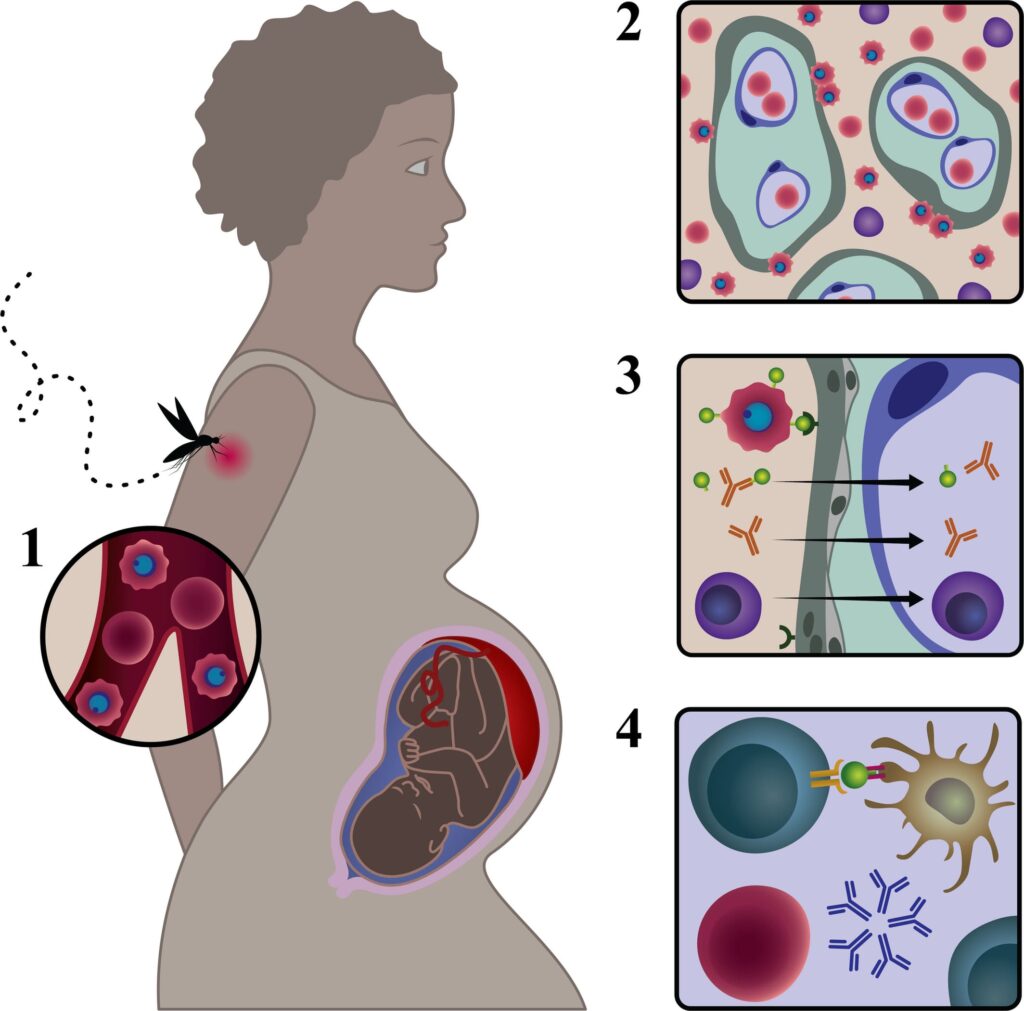

MALARIA IN PREGNANCY

Malaria is a febrile condition/disease caused by a Plasmodium parasite and is the most common cause of pyrexia in tropical regions, usually associated with rigors.

CAUSES

Malaria is caused by Plasmodium parasites (protozoa), which are of four types:

- Plasmodium falciparum: This is the most dangerous species, responsible for the majority of malaria deaths worldwide. It can cause severe complications, including cerebral malaria, which can lead to coma and death. During pregnancy, P. falciparum infections are particularly dangerous, increasing the risk of low birth weight, preterm birth, and stillbirth.

- Plasmodium vivax: This species is less deadly than P. falciparum but can still cause serious illness. It is characterized by relapses, where symptoms can reappear months after the initial infection. During pregnancy, P. vivax can cause anemia and increase the risk of miscarriage.

- Plasmodium ovale: This species is similar to P. vivax in its symptoms and ability to cause relapses. It is less common than P. vivax and P. falciparum.

- Plasmodium malariae: This species is the least common and usually causes a milder form of malaria. However, it can cause severe complications in some cases, particularly in pregnant women.

MODE OF ENTRY

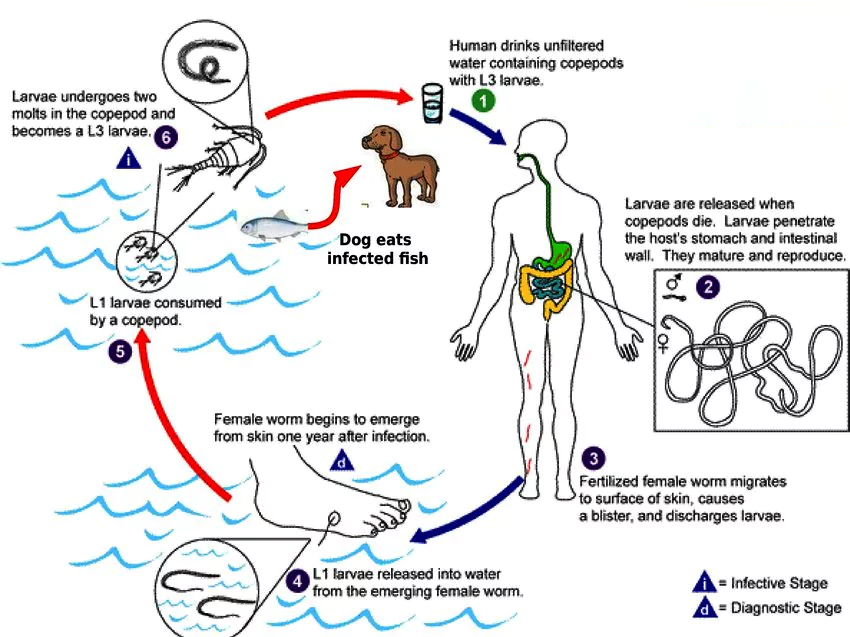

Malaria parasites are transmitted by a female Anopheles mosquito. The mosquito spits saliva onto human skin to soften it. Since malaria parasites are stored in the saliva, they are introduced through the proboscis while the mosquito sucks blood, which is used by the female mosquito for egg maturation.

MALARIA CYCLE

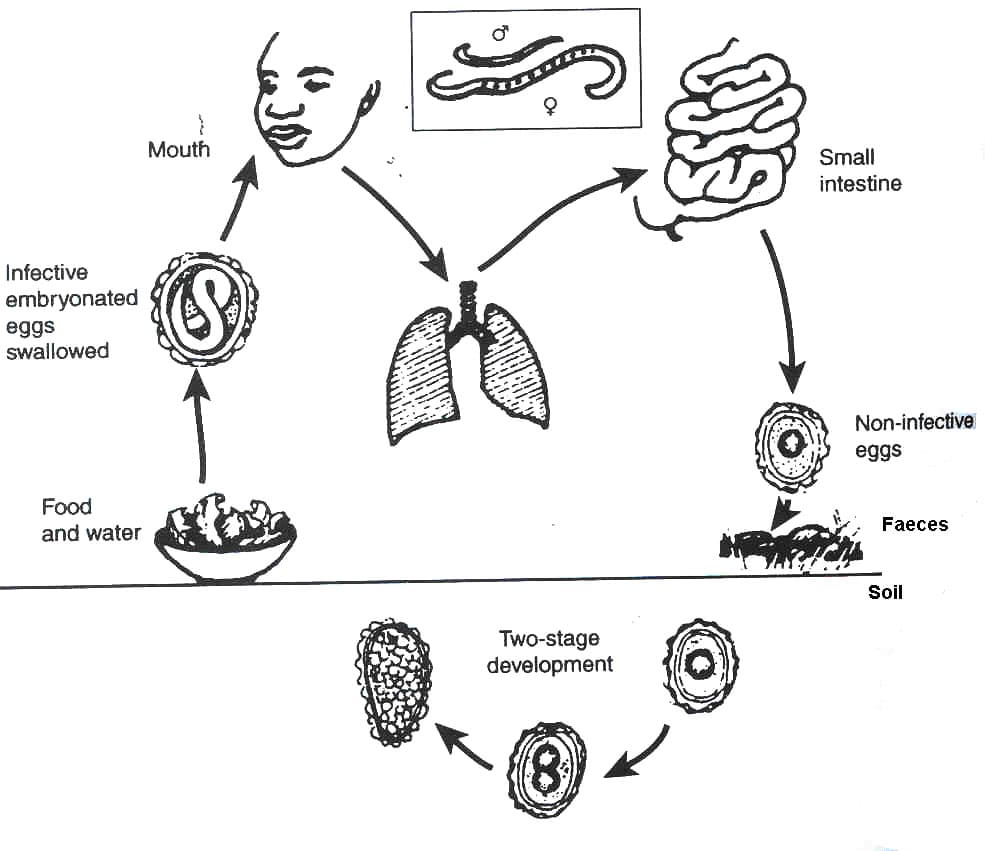

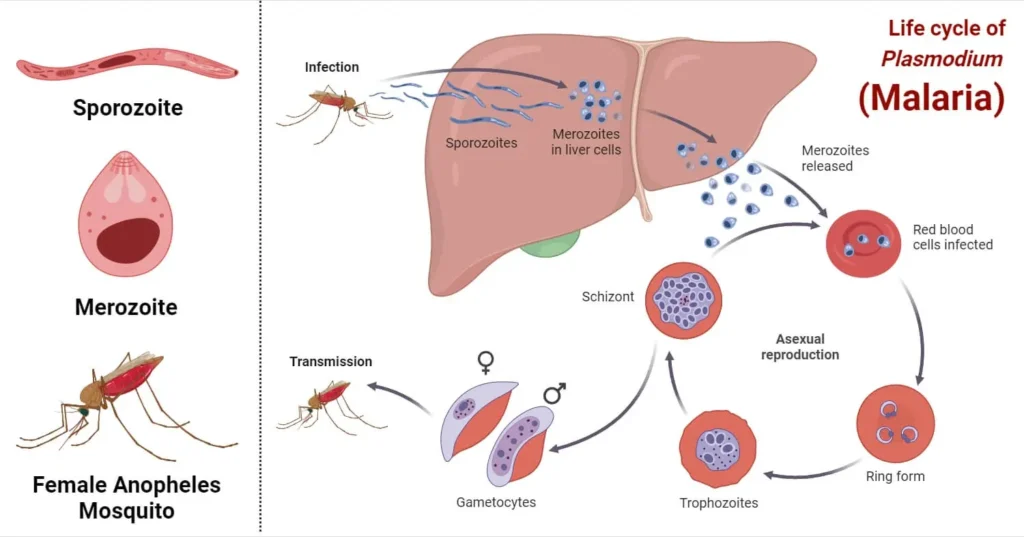

There are two cycles:

- Malaria cycle in the mosquito (Sexual stage – union of male and female gametes to form a zygote)

- Malaria cycle in humans (Asexual stage)

MALARIA CYCLE IN THE MOSQUITO (SEXUAL STAGE)

When a mosquito bites an infected person, it acquires gametocytes (sexual cells of a malaria parasite). After ingestion, these gametocytes travel through the blood to the mosquito’s stomach, where they unite and form a zygote on the stomach walls.

Zygote → Ookinete → Oocyst → Sporozoite (mature malaria parasite still within the mosquito).

The sporozoites move to the mosquito’s salivary glands, ready to be injected into a healthy person.

MALARIA CYCLE IN HUMANS (ASEXUAL STAGE)

An infected mosquito bites a healthy person, introducing sporozoites that spread within the body in approximately 30 minutes. These sporozoites enter the bloodstream and are transported to the liver for further development, known as PRIMARY TISSUE SCHIZONTS. The parasites develop and mature within liver cells, eventually destroying them. After about 7-14 days (incubation period), the parasites rupture from the liver cells as merozoites, entering the bloodstream to infect red blood cells.

Chronic malaria: Merozoites are the mature malaria parasites. They attack and feed on red blood cells until they destroy them completely, releasing waste products and causing the body to react.

CAUSES OF FEVER IN MALARIA

- Presence of malaria parasites in the body is recognized as foreign by the immune system.

- The rupture of red blood cells as the parasite destroys them triggers a response.

- The release of toxins from the parasites causes fever due to waste products and destroyed haemoglobin.

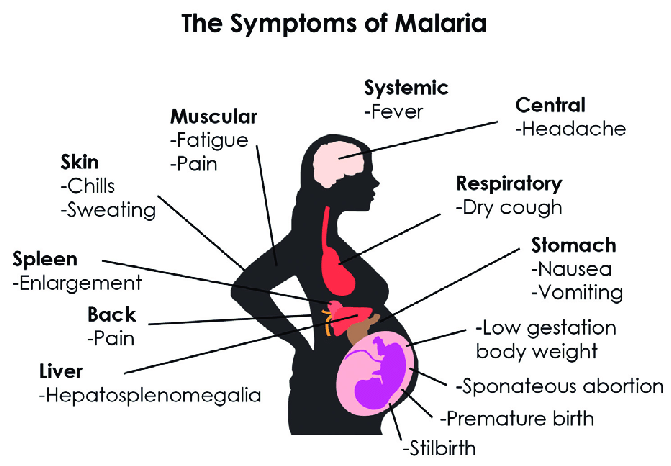

SIGNS & SYMPTOMS OF MALARIA

They range from mild to severe.

MILD TO MODERATE SIGNS & SYMPTOMS

- Fever: Low-grade fever, often intermittent or fluctuating

- Headache: Often severe and persistent

- Joint pain: Muscles and joints may ache

- Nausea and vomiting: Feeling sick to the stomach with or without throwing up

- Anorexia: Loss of appetite

- Abdominal issues: Constipation or diarrhea

- Malaise: Feeling generally unwell and weak

- Dizziness: Feeling lightheaded or unsteady

- Nightmares: Disturbing dreams while sleeping

SEVERE MALARIA SYMPTOMS:

- High fever: Persistent high temperature

- Severe headache: Intense and unrelenting headache

- Confusion and disorientation: Difficulty thinking clearly

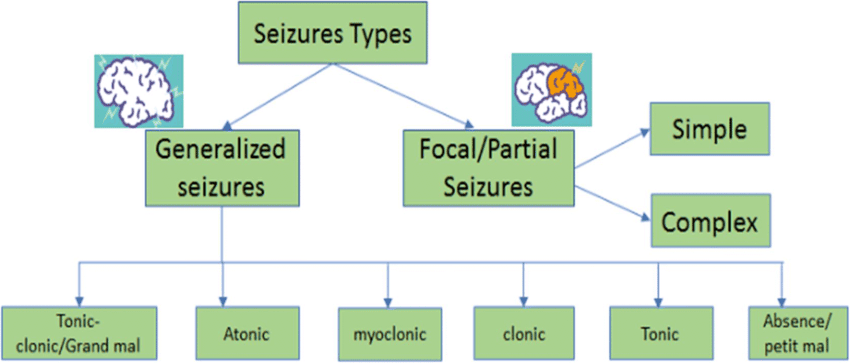

- Seizures: Uncontrolled muscle spasms

- Coma: Loss of consciousness

- Jaundice: Yellowing of the skin and eyes

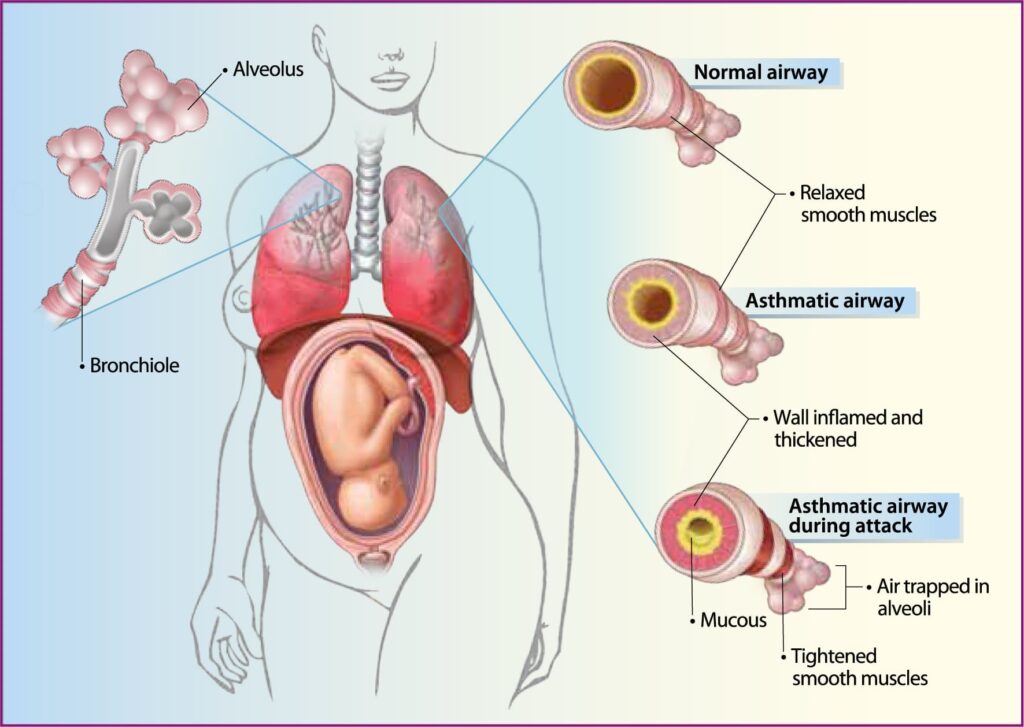

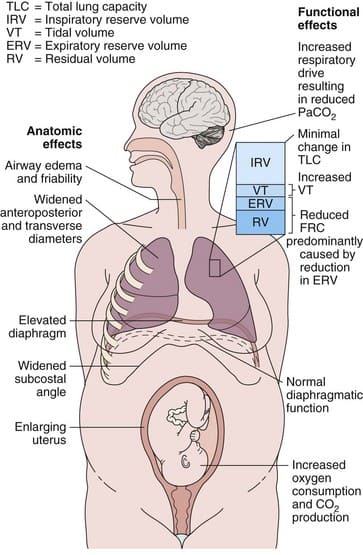

- Rapid breathing: Increased breathing rate

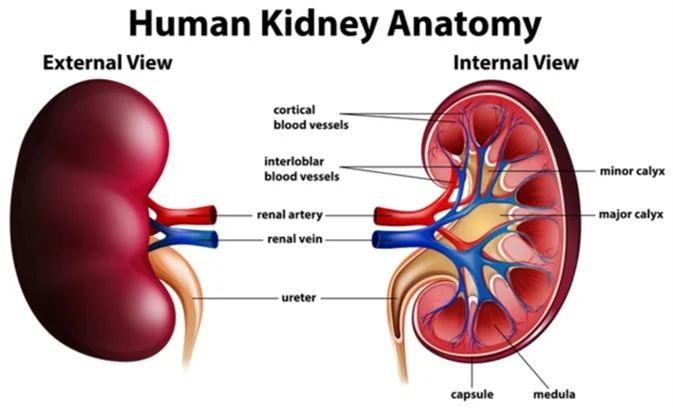

- Kidney failure: Inability of the kidneys to filter waste

- Blood in urine: Blood appearing in the urine

- Severe anemia: Low red blood cell count

SEVERE SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Can also be characterized in four stages:

- COLD STAGE: Patient feels very cold, increased pulse, nausea, and goosebumps.

- RIGOR STAGE: Shivering attacks, fast pulse, nausea, and possible vomiting.

- HOT STAGE: Temperature rises between 38-40°C, severe headache, vomiting, restlessness, and convulsions in children.

- SWEATING STAGE: Temperature lowers, sometimes to normal or subnormal levels, lasting 3-4 hours, with or without treatment.

TREATMENT OF MALARIA

Classified into:

A. Uncomplicated malaria

B. Severe and complicated malaria

C. Intermittent preventive treatment

D. Severe malaria in pregnant women and children under 4 months

Uncomplicated Malaria

- Artemether/Lumefantrine (50mg per tablet): Start with 200mg, then 100 mg daily.

- Artesunate + Amodiaquine (similar to Artemether).

Second Line

- Quinine (300mg per tablet): 600 mg dose every 8 hours for 7 days.

Severe and Complicated Malaria

- Artemisinin combination therapies (ACTs)

- Parenteral Artemether (IM or IV)

- Quinine (600mg, adjusted by body weight)

Intermittent Preventive Treatment

- Fansidar (1500mg, 3 tablets taken at once from 4 months or 16 weeks).

Severe Malaria in Pregnancy

- Parenteral Quinine (600 mg every 8 hours): Given in the 1st trimester. After the 1st trimester, ACTs can be administered.

- For children under 4 months or weighing below 5kg, Quinine is given.

SIGNS OF UNCOMPLICATED MALARIA

- Fever: Intermittent or fluctuating fever, may be low-grade or high.

- Headache: Often severe and persistent.

- Chills: Episodes of shivering and cold sensations.

- Sweats: Episodes of profuse sweating.

- Muscle aches: Muscle soreness and pain.

- Fatigue: Feeling tired and weak.

- Nausea and vomiting: Feeling sick to the stomach with or without throwing up.

- Diarrhea: Loose stools.

- Loss of appetite: Decreased hunger.

- Dehydration: Loss of body fluids, leading to dry mouth and skin.

- Abdominal pain: Pain in the stomach area.

SIGNS OF COMPLICATED MALARIA

- Severe anemia: Low red blood cell count, leading to fatigue, weakness, and pale skin.

- Jaundice: Yellowing of the skin and eyes due to bilirubin buildup.

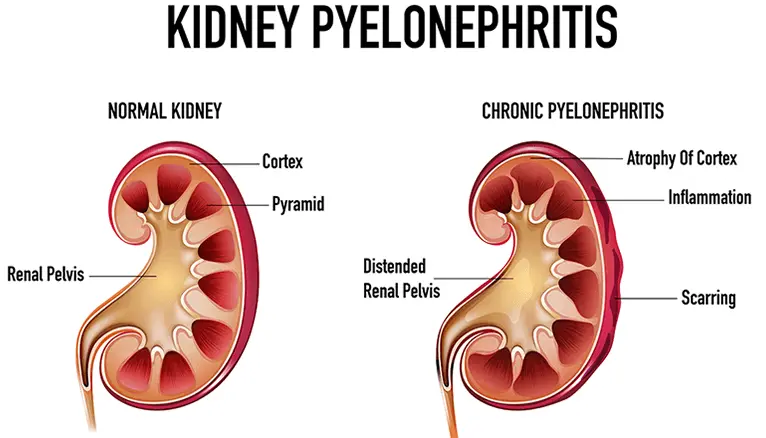

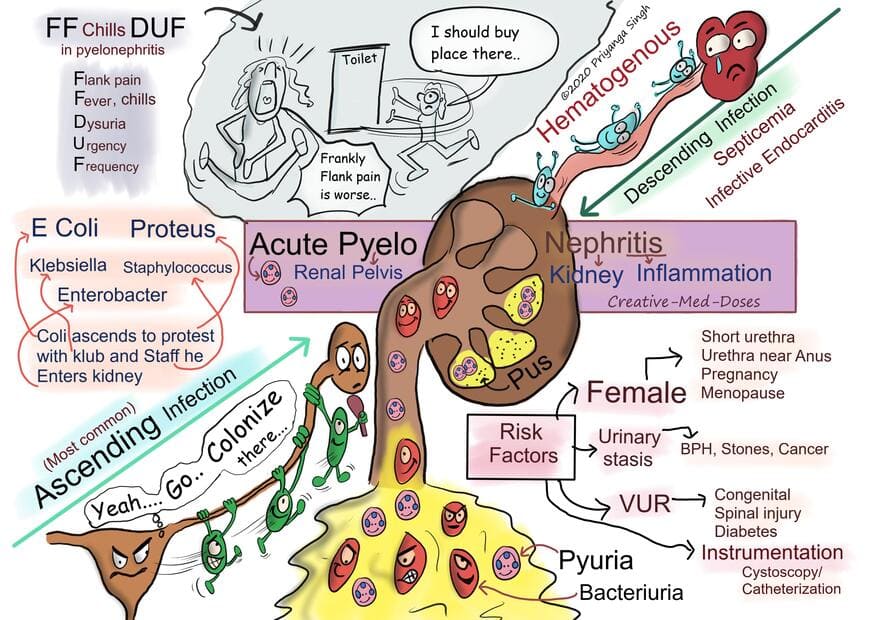

- Renal failure: Kidney failure, leading to decreased urine output and waste buildup.

- Cerebral malaria: Parasites infect brain cells, causing confusion, seizures, coma, and death.

- Pulmonary edema: Fluid buildup in the lungs, leading to difficulty breathing.

- Shock: Life-threatening condition where the body is unable to circulate blood effectively.

- Metabolic acidosis: Build-up of acid in the blood, leading to various complications.

- Hypoglycemia: Low blood sugar, potentially leading to seizures and coma.

- Respiratory distress: Difficulty breathing, including rapid breathing and wheezing.

- Bleeding: Increased risk of bleeding, including gastrointestinal bleeding.

- Behavioural changes: Confusion, disorientation, delirium, and hallucinations.

- Prostration: (trying to touch something that isn’t there)

MANAGEMENT

The midwife manages mild cases of malaria and treats it as an outpatient. She treats malaria between 16-36 weeks of pregnancy due to the new drug policy.

First Line Drug

- Refer mothers below 16 weeks and above 36 weeks of pregnancy for hospital management.

Steps for Management:

- Welcome the mother, offer a seat, greet, and introduce yourself.

- Take history (personal, problem, environment, pregnancy).

- Make observations (TPR, BP, weight) and interpret them.

- Conduct general and abdominal examinations to decide on treatment or referral.

- Treat symptoms like fever, headache, and anaemia.

- Administer appropriate medications (e.g., iron supplements, antimalarials).

NEW MALARIA TREATMENT POLICY

- Uncomplicated Malaria

- First-line treatment: Artemether or Artesunate + Amodiaquine

- Second line: Quinine

- Severe Malaria

- Parenteral Quinine

- Parenteral Artemisinin derivatives (ACTs)

- Uncomplicated/Severe Malaria in Special Groups

- Pregnant women in the first trimester are given Quinine. ACTs can be used after the 1st trimester.

- For children under four months, Quinine is given while ACTs are contraindicated.

FOR SEVERE COMPLICATED MALARIA,

- Admit the patient

- Take history (personal, pregnancy, complications)

- Inform the doctor

- Prepare for examination and treatment

- Administer emergency treatment and anti-malarial medications

- Manage complications and provide supportive care

Emergency Treatment

- Resuscitation with attention to the airway

- IV infusion introduction

- Effective anti-malarial medication administration based on body weight

- Correct hypoglycemia with Dextrose

- Correct/prevent dehydration

- Reduce high body temperature with antipyretics

- Control convulsions with Diazepam

- Determine the need for blood transfusion

Supportive Care

- Comfortable bed with a treated mosquito net

- Clean environment and proper hygiene

- Complete bed rest, daily baths, and tepid sponging

- Oral hygiene every 4 hours

- Adequate diet with small servings, sweetened foods, fruits, and vitamin supplements

- Monitor bowel and bladder functions

- Provide passive and active exercises

- Regular observations (TPR, BP, fetal heart, weight, jaundice, blood smears)

- Discharge with advice on diet, rest, medication, and mosquito net usage

COMPLICATIONS OF MALARIA

Effects on Pregnancy:

To the mother:

- Increased Risk of Severe Malaria: Pregnancy significantly increases the susceptibility to severe malaria, putting mothers at higher risk of complications like cerebral malaria, pulmonary edema, and renal failure.

- High Temperatures: Fever associated with malaria can cause intense discomfort and dehydration, particularly for pregnant women who are already experiencing hormonal changes and increased body temperature.

- Anaemia: Malaria parasites destroy red blood cells, leading to anaemia, which can be exacerbated during pregnancy when blood volume increases. Severe anaemia can lead to fatigue, weakness, and shortness of breath, further jeopardizing the mother’s health.

- Puerperal and Cerebral Malaria: These life-threatening conditions pose a high risk to pregnant women. Puerperal malaria occurs during or after childbirth, while cerebral malaria involves the brain and can lead to coma and death.

- Antepartum and Postpartum Haemorrhage: Malaria increases the risk of bleeding before or after childbirth, leading to severe blood loss and potential complications for both mother and baby.

- Ill Health and Compromised Immunity: Malaria symptoms, including nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, and loss of appetite, can affect a pregnant woman’s health and worsen nutritional deficiencies. The weakened immune system makes her more susceptible to infections.

- Jaundice and Dehydration: The buildup of bilirubin, a breakdown product of red blood cells, can cause jaundice, which further compromises the mother’s health and can impact the baby’s development. Dehydration, a common symptom of malaria, can lead to complications for both the mother and fetus.

To the baby:

- Abortions: Malaria increases the risk of miscarriage, especially during the first trimester.

- Prematurity: Malaria can trigger premature labor, leading to babies born before 37 weeks of pregnancy, increasing their risk of health problems.

- Intrauterine Fetal Death (IUFD): Malaria can lead to the death of the baby in the womb, especially in the third trimester.

- Low Birth Weight: Babies born to mothers with malaria are more likely to have low birth weight, increasing their risk of health problems and long-term developmental issues.

- Congenital Malaria: The baby can be infected with malaria parasites in the womb, leading to complications at birth or later in life.

- Intrauterine Growth Restriction (IUGR): Malaria can hinder the baby’s growth in the womb, leading to smaller size at birth, impacting their long-term health and development.

Effects on the Ward:

- Extended Hospital Stays: Malaria complications can lead to prolonged hospital stays, burdening healthcare resources and increasing the risk of infections.

- Blockage of Space for Urgent Obstetric Cases: Long stays by malaria patients can limit space and resources for urgent obstetric cases, delaying critical care for other mothers.

- Ward Congestion and Cross-Infection: Overcrowding due to malaria cases can increase the risk of cross-infection, affecting the health of other patients and healthcare workers.

- Financial Strain on Families: Treatment and hospitalization for malaria can strain the finances of families, especially in developing countries where access to healthcare is limited.

- Deprivation of Maternal Care for Children at Home: Mothers hospitalized for malaria are unable to care for their other children, potentially leading to neglect and health issues.

- Economic Inefficiency: Malaria during pregnancy not only affects individual families but also impacts economic productivity due to lost work days, reduced income, and increased healthcare costs.

MALARIA IN PREGNANCY Read More »