Table of Contents

ToggleFETAL CIRCULATION

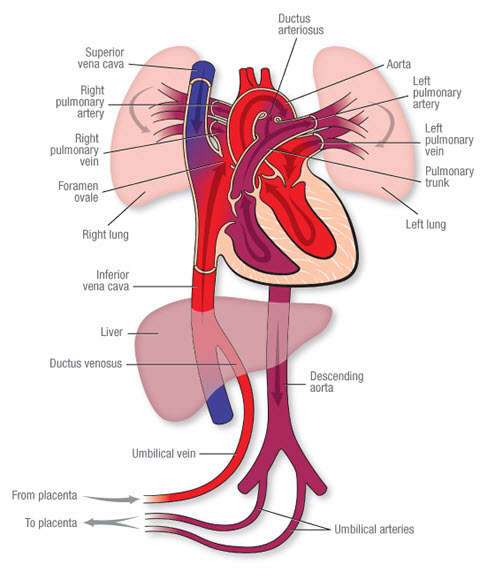

Fetal circulation is the process by which a fetus in utero receives nutrients and oxygen from the placenta for growth and development.

In utero, the fetus relies on the placenta for respiration, nutrition, and excretion. The lungs are non-functional because they are sealed off by membranes, and blood from the placenta is already oxygenated.

Important Notes:

- The fetus develops its own blood during intrauterine life; it does not mix with maternal blood except in pathological situations.

- The fetus produces its own red and white blood cells.

- During intrauterine life, the fetal gastrointestinal and respiratory systems are non-functional. The fetus obtains nutrients and oxygen from maternal blood through diffusion and osmosis, facilitated by the selective action of the cytotrophoblast and syncytiotrophoblast.

Blood Circulation in Temporary Structures:

(i) Umbilical Vein: Blood from the placenta, 80% saturated with oxygen and nutrients, is transported to the fetus via the umbilical vein. It branches in the liver, joining the portal vein and supplying the liver. This is the only vessel in the fetus carrying unmixed blood.

(ii) Ductus Venosus: Connects the umbilical vein to the inferior vena cava. Here, the blood mixes with partially oxygenated blood returning from the lower body.

(iii) Foramen Ovale: Approximately 75% of the mixed blood passes through this temporary opening between the two atria. This diversion occurs because the blood is already oxygenated and doesn’t need to go to the lungs. A small amount of blood flows through the pulmonary artery to the lungs (to maintain viability) and returns to the left atrium via the pulmonary vein. 25% of this blood enters the left ventricle and then the aorta. The heart and brain receive relatively well-oxygenated blood because the coronary and carotid arteries are early branches. The arms are more developed than the legs at birth because they receive oxygenated blood from the aorta.

(iv) Ductus Arteriosus: Moves blood from the pulmonary artery to the descending aorta, entering just beyond where the subclavian and carotid arteries branch from the aorta.

(v) Hypogastric Arteries: Blood then flows to the hypogastric arteries (branches of the internal iliac arteries), becoming the umbilical arteries, which return approximately 15% oxygen-saturated blood to the placenta for re-oxygenation.

Simplified Flow:

- Oxygenated blood from the mother enters the placenta.

- Oxygenated blood travels via the umbilical vein to the fetus.

- Most of this blood bypasses the liver via the ductus venosus.

- The blood enters the inferior vena cava.

- Most of the blood flows through the foramen ovale into the left atrium.

- The blood is then pumped to the rest of the body.

- Deoxygenated blood returns to the heart.

- Some blood goes to the lungs, but most is shunted via the ductus arteriosus to the aorta.

- Deoxygenated blood travels back to the placenta through the umbilical arteries.

Mnemonic:

P-U-D-I-F-D-U (sounds like “Poo-dee-fid-you”):

- Placenta: Receives oxygen from mom

- Umbilical Vein: Brings oxygen to baby

- Ductus Venosus: Bypasses liver

- Inferior Vena Cava: Blood mixes

- Foramen Ovale: Bypasses lungs

- Ductus Arteriosus: Bypasses lungs again

- Umbilical Arteries: Returns blood to placenta

Changes After Birth and Adaptation to Extrauterine Life:

Physiological changes after birth are initiated by inspiration and cutting/clamping of the umbilical cord.

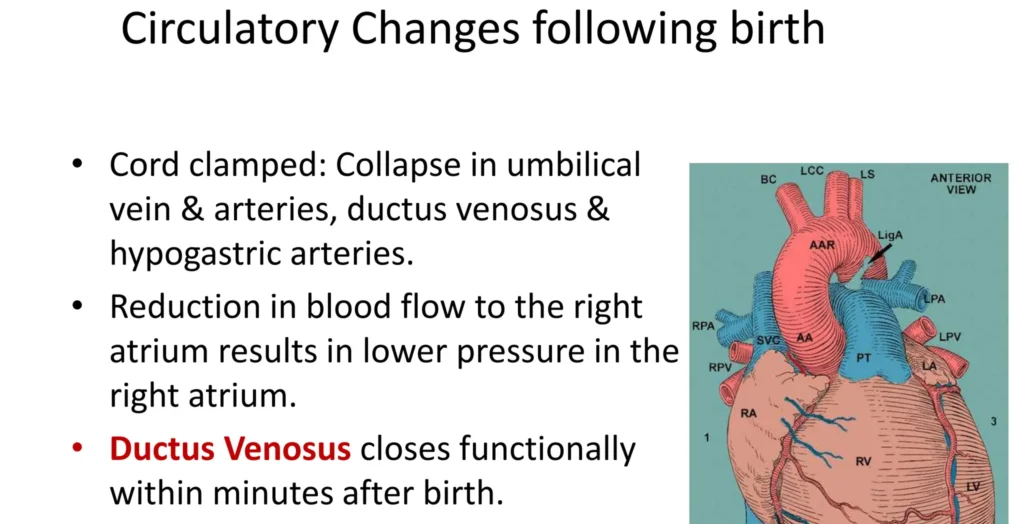

- Clamping the cord stops circulation through the umbilical vein, causing it to collapse. Its abdominal portion thromboses and occludes, forming the fibrous ligamentum teres, running from the umbilicus to the liver, enclosed in the falciform ligament.

- These changes lead to the collapse of the ductus venosus, which becomes the ligamentum venosum. Umbilical vein collapse reduces atrial pressure.

- The onset of respiration and pulmonary circulation increases right atrial pressure, closing the foramen ovale flap-like valve, which seals to form the fossa ovalis.

- When the neonate cries, lung expansion increases the vascular field. Blood that previously flowed through the ductus arteriosus to the aorta now flows through the pulmonary artery to the lungs for oxygenation. The ductus arteriosus becomes the ligamentum arteriosum.

- The hypogastric arteries contract, becoming obliterated; however, the first few inches remain patent, forming the internal iliac and superior vesicle arteries. The baby now receives nutrients through feeding and eliminates waste via the kidneys and gastrointestinal system.

CONGENITAL HEART DEFECTS (ANOMALIES)

1. Ventricular Septal Defect (VSD): Incomplete closure of the wall between the two ventricles results in mixing of oxygenated and deoxygenated blood, flowing from left to right. These defects often close spontaneously during childhood or adolescence. Large defects, however, can lead to pulmonary hypertension due to increased blood flow through the pulmonary circulation.

2. Atrial Septal Defect (ASD): Incomplete closure of the wall between the two atria causes blood mixing. The right side of the heart handles a larger-than-normal blood volume, leading to hypertrophy. Excess blood flows through the pulmonary artery to the lungs, causing higher-than-normal pressure in the pulmonary blood vessels and potentially congestive heart failure. Treatment involves open-heart surgery.

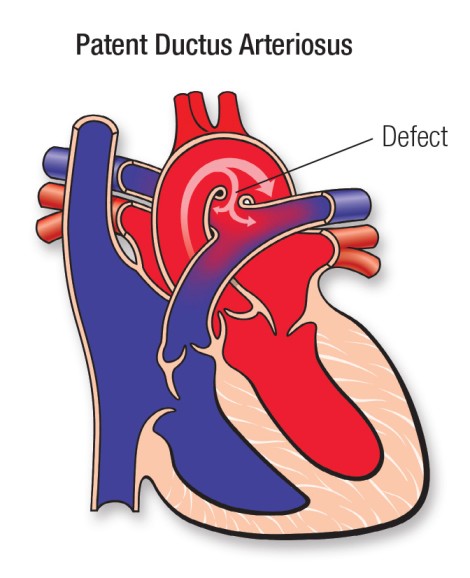

3. Patent Ductus Arteriosus (PDA): Failure of the ductus arteriosus to close creates a communication between the aortic arch and the pulmonary artery. A large, persistent PDA increases pulmonary artery pressure, potentially leading to Eisenmenger’s syndrome—a reversal of flow (right-to-left shunt). Congestive heart failure may necessitate medication to inhibit prostaglandins and promote ductus arteriosus closure.

4. Transposition of the Great Vessels: The aorta and pulmonary artery are reversed. The aorta receives poorly oxygenated blood from the right ventricle and delivers it to the body without further oxygenation. Similarly, the pulmonary artery receives well-oxygenated blood from the left ventricle but returns it to the lungs. Early surgical correction is necessary for survival.

5. Ectopia Cordis: Failure of the anterior thoracic wall to form during development results in the heart being exposed on the surface of the body.

6. Tetralogy of Fallot: This condition involves four simultaneous defects:

(i) Right Ventricular Hypertrophy: Enlargement of the right ventricle.

(ii) Ventricular Septal Defect (VSD): Communication between the two ventricles.

(iii) Overriding Aorta: The aorta originates above the VSD.

(iv) Pulmonary Stenosis: Narrowing of the pulmonary artery entrance, decreasing blood flow and causing right ventricular hypertrophy due to increased preload.

7. Coarctation of the Aorta: Narrowing or partial closure of the aorta after the ductus arteriosus closes, obstructing left ventricular blood flow. The lower body receives less blood than the upper body.

Other Defects:

- Mitral Stenosis: Narrowing of the mitral valve slows blood flow.

- Left Ventricular Hypoplasia: The left ventricle may be too small to eject a normal cardiac output. Treatment involves surgery.

- Left Ventricular Hypertrophy: Enlargement of the left ventricle.

- Prostaglandin Treatment: Used to keep the ductus arteriosus open, improving blood flow beyond a coarctation.

- Pulmonary Atresia and Tricuspid Atresia: These anomalies prevent effective blood flow from the right ventricle to the pulmonary arteries. Survival depends on a patent ductus arteriosus.

- Epstein’s Anomaly: Abnormal tricuspid valve leaflets causing blood regurgitation.

Conclusion: Congenital heart anomalies are often incompatible with life and require immediate attention.

Revision Questions:

- Describe the fetal circulation.

- Outline five temporary structures of fetal circulation.

- Explain the flow of blood in the fetus during intrauterine life.

- Describe the changes that occur within the temporary structures during adaptation to extrauterine life.

- State three differences between fetal and adult circulation.

1.fetal circulation is the process by which the fetus receives nutrient and oxygen for growth and development during intrauterine life

2.

-umbilical arteries

-ductus venosus

-foramen ovale

-ductus arteriosus

-umbilical veins

3.blood from the mother through the placenta the oxygenated blood is transported by umbilical arteries to supply the liver and in inferior vena cover through ductus venosus it then crosses from the right atrium to the left atrium through foramen ovale then to the left ventricle and pumped to right ventricle to be transported to the upper extremity through aorta which divides in carotid,subclavian ,and returns to the heart then pumped to the lungs for oxygenation through the pulmonary artery via ductus arteriosus blood then will be gassious exchange in the lungs and blood is pumped through the descending aorta which later becomes epigastric arteries then devides I to umbilical vein and back to placenta and the cycle continues

4

– closure of foramen ovale

– opening of the lungs when the baby cries

–

5.fetal receives from mother while adult is independent

Good lessons