Table of Contents

ToggleASTHMA IN PREGNANCY

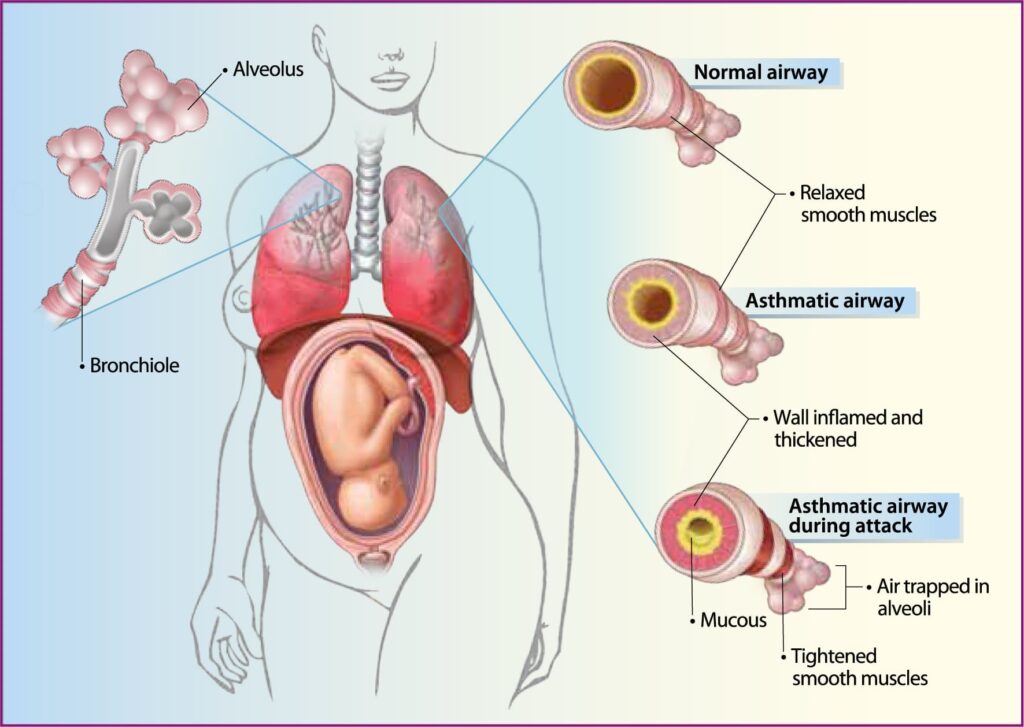

Asthma is a chronic respiratory disorder characterized by recurrent attacks of wheezing and difficulty in breathing due to reversible narrowing of the airways. Asthma flare-ups during pregnancy can cause decreased oxygen in blood, which means less oxygen reaches the baby. This put the baby at higher risk for premature birth, low birth weight and poor growth.

Causes

The exact cause of asthma is unknown, but several predisposing factors contribute to its onset. These factors include:

Predisposing Factors

- Heredity: Asthma often runs in families, suggesting a genetic predisposition.

- Infections: Respiratory infections, such as the common cold, can trigger asthma attacks.

- Psychological Factors: Emotions like fear, anger, and nervousness can lead to the release of histamines, precipitating an asthma attack.

- Allergies: Common allergens include:

- Foods

- Pollen

- Dust

- Weather changes

- Fungi

- Spores

- Feathers

- Drugs (e.g., aspirin)

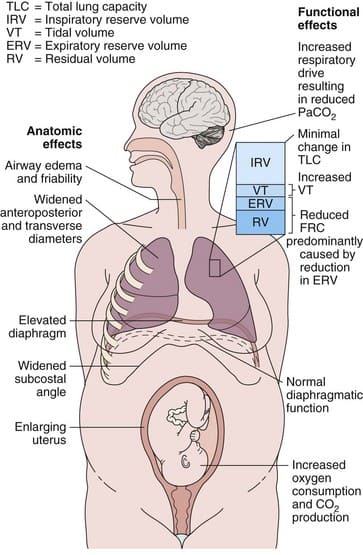

Respiratory Changes During Pregnancy

Anatomical Changes

- Upper Respiratory Tract: Increased mucosal hyperemia, edema, and glandular hyperactivity.

- Thorax and Diaphragm:

Subcostal Angle: Increases from 68 to 103 degrees in the first trimester.

Diaphragm: Rises by up to 4 cm.

Hormonal Effects on the Respiratory System

- Oestrogen: Likely responsible for tissue edema, capillary congestion, and hyperplasia of mucous glands.

- Progesterone: Contributes to improved asthma control through increased minute ventilation, smooth muscle relaxation, or cAMP-induced bronchodilation. However, it may also worsen asthma by altering beta2-adrenoceptor responsiveness and airway inflammation. Progesterone acts as a partial glucocorticoid agonist, suppressing histamine release from basophils.

- Cortisol: Maternal plasma cortisol levels increase, which may improve asthma control and reduce steroid requirements, though the effects are variable.

- Prostaglandins: Amniotic fluid contains various prostaglandins (PGE2, PGD2, PGF2-alpha). PGE2 is a bronchodilator, while others are bronchoconstrictors. The relationship between increased PGF2-alpha levels and asthma exacerbations is not well established.

Signs & Symptoms

History Taking

- Family History: A family history of asthma, allergies, or frequent upper respiratory infections, particularly in the mother, increases the risk.

- Personal History: A prior history of asthma, eczema, or hay fever can indicate a predisposition to asthma during pregnancy.

- Onset: Sudden onset of wheezing, shortness of breath, and chest tightness, especially if it’s a new experience for the mother.

- Triggers: Identifying known triggers such as dust, pollen, smoke, exercise, or certain medications can help manage the condition.

- Severity: Determining the severity of past asthma episodes, including hospitalizations or emergency room visits, can inform treatment decisions.

- Medications: Knowing current asthma medications, including inhalers and oral medications, and adherence to the treatment plan.

Examination

- Cough: May be productive (with phlegm) or dry, often worse at night or during exercise.

- Dyspnea: Difficulty breathing, shortness of breath, and feeling like you can’t get enough air.

- Chest Tightness: A constricting or squeezing sensation in the chest.

- Wheezing: High-pitched whistling sound during exhalation, sometimes heard during inhalation.

- Rhonchi: Rattling or rumbling sounds in the chest, often indicating airway inflammation or mucus buildup.

- Cyanosis: Bluish discoloration of the skin, lips, or fingernails, signifying low blood oxygen levels.

- Accessory Muscle Use: Overuse of respiratory muscles in the neck, abdomen, or chest, to aid breathing, indicating significant respiratory effort.

- Prolonged Expiration: Exhalation takes longer than inhalation due to narrowed airways.

- Tachypnea: Rapid breathing rate.

- Retractions: Pulling in of the chest wall or neck muscles during inhalation, a sign of respiratory distress.

- Agitation: Restlessness, anxiety, or confusion, often associated with low blood oxygen levels.

- Pulsus Paradoxus: A significant drop in blood pressure during inhalation, indicating severe airway narrowing.

Warning signs of Asthma Attack

History Findings:

- Cough: A persistent cough, especially if it’s dry and hacking, can be an early sign.

- Shortness of breath: Difficulty catching your breath, feeling like you can’t get enough air.

- Chest tightness: A constricting feeling in the chest, making it difficult to breathe deeply.

- Noisy breathing: Wheezing (high-pitched whistling sound), or rhonchi (rattling or rumbling sounds) during breathing.

- Nocturnal awakenings: Waking up at night due to difficulty breathing.

- Exacerbations possibly provoked by nonspecific stimuli: Triggers like dust, pollen, smoke, or exercise causing worsening symptoms.

- Personal or family history of other atopic diseases: Having a history of allergies, eczema, or hay fever can increase the risk of asthma.

General Physical Examination:

- Tachypnea: Rapid breathing.

- Retraction (sternomastoid, abdominal, pectoralis muscles): Muscles in the neck, abdomen, or chest pulling inwards during inhalation as the body tries to get more air.

- Agitation: Restlessness, anxiety, or confusion, often a sign of hypoxia (low oxygen levels).

- Pulsus paradoxus ( > 20 mm Hg): A significant drop in blood pressure during inhalation.

Pulmonary Findings:

- Diffuse wheezes: Long, high-pitched whistling sounds on exhalation and sometimes inhalation.

- Diffuse rhonchi: Short, high- or low-pitched rattling sounds during inhalation and/or exhalation.

- Bronchovesicular sounds: Abnormal lung sounds indicating airway narrowing.

Signs of Fatigue and Near-Respiratory Arrest:

- Alteration in the level of consciousness: Lethargy, drowsiness, or confusion, indicating respiratory acidosis and fatigue.

- Abdominal breathing: Using the abdominal muscles to help with breathing, a sign of respiratory distress.

- Inability to speak in complete sentences: Speaking in short, choppy phrases due to shortness of breath.

Signs of Complicated Asthma:

- Equality of breath sounds: Checking for equal air movement on both sides of the chest (signs of pneumonia, mucous plugs, or barotrauma).

- A silent chest: The absence of wheezing in someone experiencing respiratory distress can be more worrisome than the presence of wheezing.

- Jugular venous distension: Swelling of the neck veins, suggesting increased pressure in the chest cavity (possible pneumothorax).

- Hypotension and tachycardia: Low blood pressure and fast heart rate, suggesting possible tension pneumothorax.

- Fever: May indicate an upper or lower respiratory infection, which can worsen asthma symptoms.

Management of Asthma in Pregnancy

Aims of Management

- Control symptoms, including nocturnal symptoms.

- Prevent acute exacerbations.

- Ensure no limitations on activities.

- Maintain (near) normal pulmonary function.

- Protect the mother and fetus from adverse effects.

Preventive Measures

When the patient is not experiencing an attack, prevention is very important. The following advice is given:

- Education: Inform the patient about asthma and identify potential triggers.

- Avoidance of Triggers: Avoid substances that trigger attacks (varies by individual).

- Warm Clothing: Use warm clothes, such as scarves, in cold weather.

- Emotional Control: Learn to manage emotions to prevent attacks.

- Deep Breathing Exercises: Practice exercises to ensure full lung expansion.

- Medication: Always have a supply of prescribed drugs (e.g., inhalers) according to the prescriptions.

Emergency Management

If the patient is experiencing an attack, treat it as an emergency:

- Admission: Quickly admit the patient in an upright position and administer oxygen if available.

- Reassurance: Reassure the patient and relatives to reduce anxiety, which can exacerbate the condition.

- Ventilation: Ensure proper ventilation and inform the doctor.

- Medical Treatment:

- Bronchodilators: Administer intravenous Aminophylline (250-500mg every 8 hours, given slowly over 20 minutes). Nebulized salbutamol (4mg every 8 hours), which may later be replaced with ordinary inhalers.

- Corticosteroids: Hydrocortisone (100mg intravenously every 8 hours), later changed to oral prednisolone.

- Antihistamines: Piriton or Phenergan to reduce allergic reactions and congestion.

- Antibiotics: Crystalline penicillin (2ml every 6 hours) or Ampicillin (500mg every 6 hours) to prevent or treat respiratory infections.

- Intravenous Fluids: Administer dextrose 5% to prevent dehydration and provide energy.

Quick Relief for All Patients

- Short-acting bronchodilator: 2-4 puffs of short-acting inhaled beta-agonist(Such as Salbutamol) as needed for symptoms. Intensity of treatment depends on the severity of exacerbation; up to 3 times at 20-minute intervals or a single nebulizer treatment as needed. A course of systemic corticosteroids may be needed. Use of short-acting inhaled beta-agonist more than 2 times a week in intermittent asthma (daily, or increasing use in persistent asthma) may indicate the need to initiate or increase long-term control therapy.

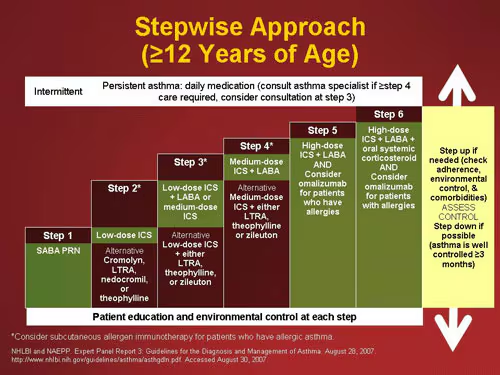

Step Ladder Management

- Step 1: Occasional use of inhaled short-acting beta2-adrenoceptor agonist bronchodilators.

- Step 2: Introduction of regular preventer therapy, preferably inhaled corticosteroids (ICS).

- Step 3: Add-on therapy with long-acting beta2-agonists (LABAs), such as salmeterol and formoterol.

- Step 4: Poor control with Step 3: Addition of a fourth drug, such as leukotriene receptor antagonists or theophyllines.

- Step 5: Continuous or frequent use of oral steroids.

Non-Pharmacological Management

Patient Education

- Explain that it is safer for pregnant women with asthma to take asthma medications than to have ongoing symptoms or exacerbations.

- Reassure that safe and adequate asthma treatment is possible during pregnancy and that good asthma control minimizes the risk of complications.

Smoking Cessation

- Smoking increases the risk of asthma exacerbations, bronchitis, or sinusitis, and necessitates an increased need for medication.

- Associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes, including spontaneous pregnancy loss, placental abruption, preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM), placenta previa, preterm labor and delivery, low birth weight, and ectopic pregnancy.

Control of Environmental Triggers

- Reduce the need for pharmacologic intervention by avoiding exposure to allergens and nonspecific airway irritants like tobacco smoke, dust, and environmental pollutants.

- Particular allergens of concern include dander from pets and antigens from household dust mites.

Nursing Care

Bed Rest: Complete bed rest is essential, with assistance provided for all activities due to dyspnea.

- Maternal Positioning: Pregnant patients with acute asthma should rest in a seated or lateral position to avoid aortocaval compression by the gravid uterus, particularly in the third trimester.

- Hydration: Intravenous fluids are not necessary unless the patient cannot maintain oral hydration.

- Supplemental Oxygen: Initially 3 to 4 L/min by nasal cannula, adjusting to maintain a PaO2 of at least 70 mmHg and/or oxygen saturation of 95% or greater.

Observation: Monitor fetal condition and mother’s response to treatment closely.

Management Of Acute Attacks Of Asthma (Asthma Exacerbation) In Pregnancy

- Avoidance of asthma triggers (allergens, irritant) to minimize airway inflammation and hyper-responsiveness.

- Oxygen inhalation with mask to maintain Oxygen saturation > 95% (pulse oximeter).

- High dose albuterol by nebulization every 20 minutes and inhaled ipratropium bromide and systemic corticosteroid.

- Repeat assessment of symptom, physical examination and Oxygen saturation to be done.

- Corticosteroids: Intravenous hydrocortisone 200 mg stat and to be repeated after 4 hours. Because of long onset of action, corticosteroids should be given along with β2-agonists.

- Mechanical ventilation is needed for status asthmaticus to avoid hypoxemia and carbon dioxide retention.

Pharmacotherapy in Exacerbations

- Agents: The recommended agents include inhaled short-acting beta-agonists e.g Albuterol (ProAir, Ventolin), levalbuterol (Xopenex), terbutaline (Brethine). These are often given via nebulizer or metered-dose inhaler (MDI), inhaled anticholinergic agents e.g Ipratropium bromide (Atrovent), oral or intravenous glucocorticoids Oral prednisone or methylprednisolone (Solu-Medrol).

- Systemic Glucocorticoids: Benefits outweigh risks in preventing life-threatening asthma exacerbations e.g Dexamethasone.

- Ipratropium: Used to treat severe acute asthma exacerbations.

- Intravenous Magnesium Sulfate: Magnesium sulfate can be used in severe, life-threatening asthma exacerbations, especially in those who haven’t responded well to other treatments. It has bronchodilating and anti-inflammatory effects.

Asthma Management During Labor and Delivery

- Only 10-20% of women develop an exacerbation during labor and delivery.

- Opiate analgesics should be avoided as they are bronchoconstrictor and respiratory depressant. Maternal oxygenation should be adequately maintained. Labetalol should be avoided as it may precipitate asthma.

- Hydrocortisone 100 mg IV 8 hourly during labor and 24 hours postpartum is to be given if the patient had steroids within the previous 4 weeks. Inhaled corticosteroid (fluticasone, budesonide) prevents bronchial hyper-responsiveness to allergens.

- Syntocinon is better than ergometrine because of bronchoconstrictor effect of the latter. PGF2 α should not be used, as it precipitates bronchospasm. PGE1 and PGE2 compounds can be used locally for induction of labour or abortion.

- Epidural anesthesia is preferable to general anesthesia because of risk of atelectasis and subsequent chest infection following the latter. Halothane is better in general anesthesia. However, it produces uterine atony.

- Ketamine is used for induction of general anesthesia as it prevents bronchospasm.

- Oxygen saturation is assessed with pulse oximeter or arterial blood gases.

- Postnatal physiotherapy is maintained and drugs are continued.

- Breastfeeding should be encouraged, as it delays the onset of allergic problems in the child. Drugs used in asthma: Prednisolone, corticosteroids, LABA, LTRA do not contraindicate breast feeding.

- Contraception: Barrier method is the best. For terminal contraception, husband is to be motivated for vasectomy.

Peripartum Care

- Oxytocin: The drug of choice for labor induction and postpartum hemorrhage control.

- Pain Control: Avoid morphine and meperidine; use fentanyl or butorphanol. Epidural anesthesia is preferred; if general anesthesia is needed, use ketamine due to its bronchodilatory effect. Avoid ergot derivatives.

- Monitoring: Monitor blood glucose levels in the baby if high doses of short-acting beta-agonists were used during labor and delivery.

Effects of Asthma on Pregnancy

- Infections: Increased susceptibility due to lowered resistance.

- Physiological Changes: Nervous system changes can lead to frequent attacks.

- Complications:

- Exhaustion, stress, cyanosis, and dyspnea can cause intrauterine hypoxia.

- Rapid pulse, tachypnea, and lowered blood pressure.

- Mental confusion due to reduced oxygen to the brain.

- Placental insufficiency leading to intrauterine growth retardation.

Maternal Risks:

- Hyperemesis (severe nausea and vomiting): Asthma medications, particularly inhaled corticosteroids, can contribute to nausea and vomiting.

- Accidental haemorrhage: Increased risk of bleeding during pregnancy since some asthma features can predispose mother to trauma.

- Respiratory failure: Severe asthma attacks can lead to respiratory failure, requiring mechanical ventilation.

- Pregnancy-induced hypertension (PIH): Asthma may increase the risk of developing PIH, a serious condition characterized by high blood pressure during pregnancy.

- Preterm labour and premature birth: Asthma exacerbations can trigger contractions and lead to early delivery.

- Increased risk of maternal death: Severe asthma complications, particularly respiratory failure, can be life-threatening.

Effects on Labor

- Status Asthmaticus: An attack that does not respond to usual treatment.

- Fetal Asphyxia: Due to constriction of blood vessels in the lungs.

- Maternal Distress: Significant distress and potential obstetric shock.

- Assisted Delivery: Necessary due to the mother’s inability to push effectively.

Effects on the Baby

- Oligohydramnios (low amniotic fluid levels): Asthma medications can affect the baby’s fluid balance, potentially leading to low amniotic fluid.

- Low birth weight (LBW): Premature birth, which is more common in women with asthma, is a major factor contributing to LBW.

- Premature delivery: Asthma can increase the chances of delivering before the full term of pregnancy.

- Fetal demise (death): Severe asthma complications, particularly during the third trimester, can lead to fetal distress and death.

- Meconium staining (indicating fetal distress): Fetal distress can cause the baby to release meconium (first stool) into the amniotic fluid.

Neonatal Risks:

- Neonatal hypoxemia (low oxygen levels): Premature babies born to mothers with asthma are more likely to experience low oxygen levels at birth.

- Low newborn assessment scores: Prematurity and low oxygen levels can negatively impact the baby’s apgar score.

- Increased perinatal mortality: Premature birth and complications associated with asthma can increase the risk of infant death.

Complications

- Cardiac Failure: Due to the increased strain on the heart.

- Respiratory Failure: Severe and untreated attacks can lead to respiratory failure.

- Poor Lactation: Due to the physical stress and medication.

- Chronic Bronchitis: Frequent attacks may lead to chronic bronchitis.

- Atonic Uterus: Resulting in prolonged labor or postpartum hemorrhage.

- Abortions and Premature Labor: Due to the stress and physical demands of asthma.

- Neonatal Complications: Various complications can arise due to the mother’s condition.